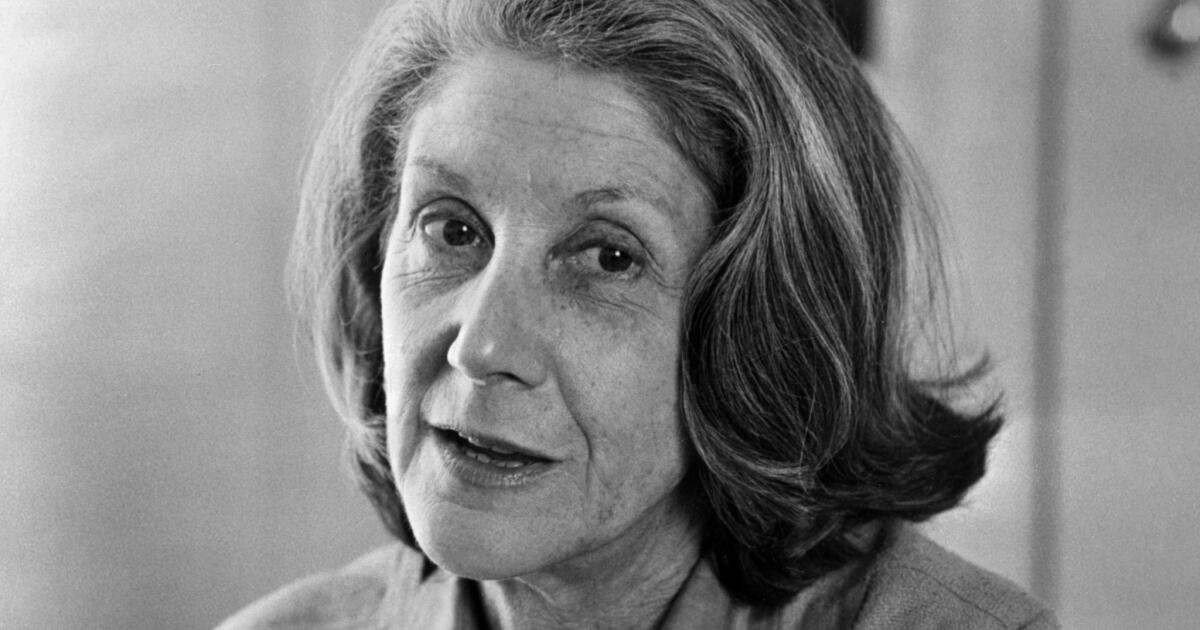

Part of the Process: Nadine Gordimer

Part of the Process is a series in which we chronicle the often turbulent, usually absurd and always interesting lives of authors we admire. It’s not easy to be a writer in the 21st century, but in a strange way, reading about the trials and tribulations of those who seem to have ‘made it’ can be a reminder that it has always been a difficult process.

The phrase household name has various connotations around the globe, and Nadine Gordimer may not always come to mind outside of South Africa. Yet, she is a writer whose impact and importance in the past century needs far more attention. From a prolific career to outspoken political activism to Nobel recognition to being almost forgotten and out of print in various places before recent revivals of sorts, her work has been immensely significant in South Africa and beyond.

Gordimer was born in 1923 in Springs, a mining town close to Johannesburg, to a Lithuanian Jewish father and an English mother. She was educated at a Catholic convent school, but her mother kept her largely home-bound as a child, due to the fear that she had a weak heart. Due to this, she began to develop a great interest in writing and reading, publishing work beginning with children’s stories from the age of 13. As a child, she also witnessed her mother’s concern about poverty and racial discrimination, as well as first-hand government repression when the police raided her family home, confiscating letters and diaries from a servant's room.

Gordimer studied for one year and University of the Witwatersrand, mixing with professionals across the colour bar and becoming interested in anti-apartheid politics. She didn’t complete her degree, but moved to Johannesburg, where she began publishing in local magazines. In 1951, the New Yorker accepted a story by her, beginning a long and beneficial relationship. Her first novel, The Lying Days, was published in 1953.

Her first publisher, Lulu Friedman, introduced her to various other anti-apartheid writers in Johannesburg. The arrest of her best friend, Bettie du Toit, in 1960, as well as other political events including the Sharpeville massacre, pushed Gordimer into active participation in the anti-apartheid movement. She was close friends with Nelson Mandela’s defence attorneys during his 1962 trial, and helped him edit his famous speech given from the defendant’s dock when he was sentenced to jail. When he was released from prison over two decades later, Gordimer was one of the first people he wanted to see.

Over the next decade, living primarily in Johannesburg and teaching at various universities in the USA, Gordimer achieved literary recognition, winning various awards and vocally advocating against apartheid. Perhaps due to this, the South African government banned several of her works, two of them (A World of Strangers and The Late Bourgeois World) for lengthy periods of time.

Gordimer joined the African National Congress when it was still listed as an illegal organisation by the South African government, even reportedly hiding ANC leaders in her home while also regularly taking part in anti-apartheid demonstrations, speaking out against government censorship and refusing to let her work be broadcast by the state broadcasting corporation. Through this time, her international reputation continued to grow after she won the Booker Prize in 1974 for The Conservationist, and then the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1991.

Gordimer had a daughter, Oriane, by her first marriage in 1949 to Gerald Gavron, a local dentist, who she divorced within three years. In 1954, she married Reinhold Cassirer, a highly respected art dealer who established the South African Sotheby's and later ran his own gallery until his death in 2001. They had one son, Hugo, who is a filmmaker. In her unauthorised biography, one of the reasons Gordimer disavowed the biographer was because of an account of an affair she had in the 1950s.

After apartheid was revoked, Gordimer continued to campaign for various causes in South Africa, most notably the HIV/ AIDs epidemic and the government’s mishandling of it. She was also an active member of various national and international literary organisations, notably PEN International. In 2006, Gordimer was attacked in her home by robbers, sparking outrage in South Africa, although Gordimer apparently still refused to move into a gated complex against the advice of some friends.

Gordimer passed away at 90 in 2014, but the legacy of her work remains complex and powerful. She wrote fifteen novels and hundreds of short stories, and always pursued the questions of how to integrate everyday life and political activism through her stories. But because so much of it was topical and political, she is sometimes seen as a ‘relic’ today despite her outsize influence in South Africa and beyond.